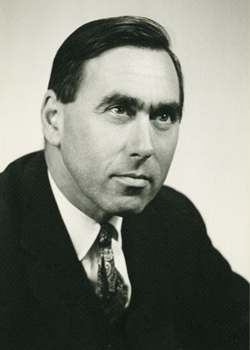

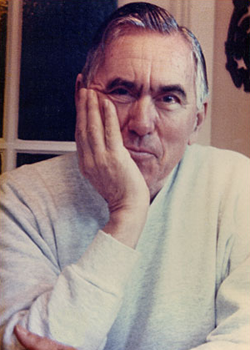

Wolfgang Lederer

Wolfgang Lederer

Biography: Wolfgang Lederer was born in Vienna, in l9l9, into a well-to-do Jewish family. He graduated from the Akademische Gymnasium with honors in the spring of l937. That September, he entered the Austrian Army as a “one year volunteer”, but upon the German occupation of Austria, in l938, he refused to take the oath on Hitler and was discharged to “service without a weapon.” Facing deportation to a concentration camp, he fled to Paris, where his older brother offered him shelter. There he attended the Sorbonne, and in the spring of l939 was awarded the Certificat de Chimie Generale, “avec mention” (with honors). But his permit to stay in France was not likely to be renewed.

A search for alternative countries of refuge proving futile, it was the fortuitous acquaintance with Professor Charles Gulick, Economics Dept., UC Berkeley, which enabled Lederer to immigrate to the United States in the summer of l939. He arrived in New York penniless, but thanks to an equally fortuitous opportunity he was able to co-drive across the entire continent with Professor Egon Brunswick, Psychology Dept., UC Berkeley. Arriving in Berkeley he was warmly received and given room and board by the ZBT fraternity, in return for making beds and cleaning bathrooms. He was granted free tuition and enrolled at the University. Within days the newspapers headlined Germany’s invasion of Poland, and England and France declared war on Germany. Intent on fighting back against Hitler, Lederer hitchhiked to Vancouver and applied at the Canadian Air Force to fly Mosquito Bombers – the only Canadian weapon then in active combat. He received a friendly response: “Would love to have you, but according to your Austrian passport you are an enemy alien.” He returned to Berkeley, where he studied Biochemistry, and he survived a penniless summer by working in a steam laundry in South Los Angeles.

Service Time: He graduated with a Bachelors degree in Biochemistry in February of l94l, and immediately enlisted in the U.S. Army at the Presidio of Monterey. Stationed at Fort Ord, he was assigned to a horse-drawn artillery regiment equipped with World-War-One “Seventy-fives”. It was manned by middle-aged professional soldiers who treated him most kindly, taught him the Manual-of-Arms with broom-sticks, and did not resent his fairly rapid promotion from Buck-Private to Staff Sergeant. After Pearl Harbor, he was briefly assigned to defend San Jose against air attacks—with a small detachment of two never-fired Browning Automatic Rifles: another example of the Armed Forces’ total unpreparedness at that time; but the following months produced an exhilarating outpouring of armaments, from Jeeps to trucks to guns.

Instant naturalization of service-members becoming possible, Lederer became a U.S. citizen and at his specific request was sent to the Armored Force School at Fort Knox, KY, to become a “Ninety-day Wonder.” He graduated a 2nd Lieutenant, and was assigned to the 702nd Tank Destroyer Battalion, attached to the 2nd Armored Division, at Fort Bragg, N.C. The “Tank Destroyers” of the Battalion were WWI primitives, and when the Division shipped out to North Africa, the “Seven-o-Deuce” was left behind; but eventually the battalion was equipped with the M-10, for some time the best Tank Destroyer in the US Army (but still inferior to German tanks). Lederer was promoted to lst Lt., then Captain, and Battalion Intelligence Officer. In January of 1944, he shipped with the Battalion on the Ile de France (a luxury liner converted to packed troop ship) from Halifax across the U-boat infested Atlantic to England. The battalion was stationed at Tidworth Barracks in the South of England until, on D plus 2, it landed on Omaha Beach as part of the 2nd Armored Division. Having been appointed Battalion Liaison-Officer to the Navy, Lederer was tasked with being the first of his Unit to jump from the Landing-ship into the uncertain waters of the beach, in order to report the Battalion’s arrival to the Beach Master. To the accompanying music of major explosions—clearly, he was finally under fire—and with a feeling of glorious triumph—a refugee returning as conqueror!—he raced across the sand some distance and found what he was looking for: a British Captain, stolid and tranquil, a worthy representative of the Queen, who accepted his report and recorded it. Then, dispatching Lederer back to his ship, he said: “By the way, you really should pay attention to those colored tapes and stay between them, the rest has not yet been cleared. You hear the sappers blowing up landmines, don’t you?” Well—beginners luck; he had miraculously failed to get himself blown up. Staying between the tapes, he returned to his LST safe and sound.

In the following months he participated in the break-through at St. Lo, in the battle of the Falaise Gap, and in the advance through Northern France, Belgium, and Holland. He was appointed Company Commander of Company C, a unit which was equipped with the new M-36 Destroyers, the most effective armored vehicle against German heavy tanks, and much in demand by the Brigade. His Company became intensely engaged in the Battle of the Bulge, then moved back North to prepare an offensive toward Cologne. This involved frantic activity, and one very dark night, sleep-deprived and exhausted, Captain Lederer, returning from the front and anxious to avoid an oncoming column of armored vehicles in the narrow streets of Aachen, pulled over on a sidewalk and promptly fell asleep in his command jeep. He awoke to find himself crushed by a friendly tank moving up to the front line. He suffered several fractures and soft tissue injuries along his left body and was evacuated to a field hospital. Encased in a body cast, he was then moved to England, and eventually by hospital ship to the United States, and by train to Fort Lewis, WA. Eighteen months of excellent care, surgical corrections and physiotherapy resulted in rehabilitation with few remaining defects. Lederer retired from service at Van Nuys, CA with the rank of Major, two Bronze Stars, and a Purple Heart.

Based on his wartime experiences, Lederer decided to become a physician and returned to UC Berkeley for two semesters of Pre-Med. He was then admitted to the University of Rochester, N.Y., Medical School. After graduating as an MD four years later, he served one year in Internal Medicine at University Hospitals in Minneapolis; one year in Psychiatry at University Hospitals, Cleveland; one year as Senior House Officer at the Maudsley Hospital, London; one year in Child Psychiatry at Children’s Hospital in San Francisco; and one year as Fellow at the Mt. Zion Psychiatric Clinic.

During this last year, he encountered Alexandra Botwin, a psychology graduate of the Sorbonne in Paris, and a Ph.D in clinical psychology from Cornell University. She was ten years younger than he, and endowed with irresistible charm; raised in Bucharest and Jewish, of Russian émigré parents, she had faced the threats of extermination under the German occupation, annihilation from bombardment by US Liberator bombers, and rape by advancing Soviet infantry. In addition, it turned out, she was just now reading the same novel by Simone de Beauvoir – as yet untranslated from the French – which Lederer was just reading; a soul mate! And beautiful! They had their first martini at The Top of the Mark and were married ten days later.

During this last year, he encountered Alexandra Botwin, a psychology graduate of the Sorbonne in Paris, and a Ph.D in clinical psychology from Cornell University. She was ten years younger than he, and endowed with irresistible charm; raised in Bucharest and Jewish, of Russian émigré parents, she had faced the threats of extermination under the German occupation, annihilation from bombardment by US Liberator bombers, and rape by advancing Soviet infantry. In addition, it turned out, she was just now reading the same novel by Simone de Beauvoir – as yet untranslated from the French – which Lederer was just reading; a soul mate! And beautiful! They had their first martini at The Top of the Mark and were married ten days later.

Over several years, Dr. Lederer maintained a private practice in San Francisco while serving on the staff of the UCSF Medical School. He supervised psychiatric residents at the Langley Porter Institute in weekly sessions, occasionally discussed clinical cases with residents of the San Francisco Veterans Administration, and for several years did the same in monthly meetings at the Mendocino State Hospital. (One of these was published in “Frontiers of Hospital Psychiatry”, l964). He lectured several times at the Psychiatry Department of UCSF and on a number of occasions gave the main talks at the yearly meetings of the Northern California Psychiatric Association: at Yosemite (published in “The Northern California Psychiatric Physician”, l988), at Pebble Beach, Santa Fe, and Ashland. The last of these, “Some Words Not Used in Psychotherapy,” was translated into French and published in PSYCHOTHERAPIES, l993. He also presented papers at conferences in Israel, in New York (“Man’s Dream: Myth and Reality” published by the Radcliffe Club, l975), and in Singapore, (“The New Patient in San Francisco”, published in the Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, l979) and, together with Alexandra Botwin: “Where Have All The Heroes Gone?”, which was then reprinted as Chapter l2 in MEN IN TRANSITION, l982.

At the request of the German Consulate in San Francisco, he evaluated over one hundred Holocaust survivors to determine whether they were entitled, under German law, to compensation for lasting psychological damage. The results were presented at the l964 meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in Los Angeles and published as “PERSECUTION and COMPENSATION: Theoretical and Practical Implications of the Persecution Syndrome”, in the Archives of General Psychiatry, l965. A related paper in German titled ENTWURZELUNGSDEPRESSION OHNE DEPRESSION, Fettleibigkeit und andere. psychosomatische depressions-Equivalente, was published in “Der Nervenarzt”, l965.

Lederer’s contributions to Journals include “Primitive Psychotherapy” (published in PSYCHIATRY, l959, and reprinted in RELIGIOUS SYSTEMS AND PSYCHOTHERAPY, l973), “Value-Oriented Psychotherapy ” (Western Behavioral Sciences Institute, l961, reprinted in MORALITY AND MENTAL HEATH, l967.) “Oedipus and the Serpent” (The Psychoanalytic Review, l964-65), “Historical Consequences of Father-Son Hostility” (The Psychoanalytic Review, l967); “The Decline of Manhood: Adaptive Trend or Temporary Confusion?” (Psychiatric Opinion, l979); “Some Moral Dilemmas Encountered in Psychotherapy” (PSYCHIATRY, l971, reprinted in CREATIVE PSYCHOTHERAPY, l976). “What if there is no Cure?” (THE PROGRESSIVE, l970, reprinted in Social Service Outlook, l971); “On Choosing a Therapist” (Psychology Today, l97l); “Speaking of Youth” (The Progressive, 1968, reprinted in The American Review, l969); “Stalking the Demons, A Psychiatrist Reflects on his Resident” (The Progressive, l967); “The Crime of Innocence” (Review of “Power and Innocence” by Rollo May, in The Progressive, l973); “How Does One Cure a Soul?” (The College, St.John’s, l976) “What Good and What Harm Can Psychoanalysis Do?” (The St.John’s Review, l984). He also wrote Chapt.l9, “Counter-Epilogue” in MEN IN TRANSITION, l982, and published l0 Book reviews in various Journals.

Dr. Lederer is the author of five books. The first of these, Dragons, Delinquents and Destiny, an Essay on Positive Superego Functions, (International Universities Press, l964), was glowingly reviewed in The Psychoanalytic Review, l966. His next, THE FEAR OF WOMEN – (Grune & Stratton, l968)—a historico-anthropologico-psychological study—found wide acclaim and was frequently quoted in feminist publications. Its Chapt. 28 was reprinted in BIRTH (l973); the entire book was also published in French, (“Gynophobie ou la peur des femmes”), Editions Payot, l970; and in Italian, (“Ginophobia: La paura delle donne”, Feltrinelli, l973). There followed “THE KISS OF THE SNOW QUEEN—Hans Christian Andersen and Man’s Redemption by Woman,” published by The University of California Press, Berkeley, l986.

Dr. Lederer is the author of five books. The first of these, Dragons, Delinquents and Destiny, an Essay on Positive Superego Functions, (International Universities Press, l964), was glowingly reviewed in The Psychoanalytic Review, l966. His next, THE FEAR OF WOMEN – (Grune & Stratton, l968)—a historico-anthropologico-psychological study—found wide acclaim and was frequently quoted in feminist publications. Its Chapt. 28 was reprinted in BIRTH (l973); the entire book was also published in French, (“Gynophobie ou la peur des femmes”), Editions Payot, l970; and in Italian, (“Ginophobia: La paura delle donne”, Feltrinelli, l973). There followed “THE KISS OF THE SNOW QUEEN—Hans Christian Andersen and Man’s Redemption by Woman,” published by The University of California Press, Berkeley, l986.

A voluminous work, “Patriarchs, Kings and Prophets, a Biblical History of the Jews for Not Very Religious Youngsters and Their Parents,” has so far remained unpublished. An abiding interest led to a chapter, “Love in Society: Thomas Mann’s Early Stories”, in A COMPANION TO THE WORKS OF THOMAS MANN, Camden House, 2004. The full extent of this interest, a large manuscript titled:” DISORDER AND EARLY LOVE—The Eroticism of Thomas Mann,” may at this writing be taking shape as a real book. Whether it will emerge into society, shiny and expensive, before its ancient author relinquishes the light of day—this remains to be seen.

In the course of the years Lederer was promoted from Instructor to Clinical Professor in the Dept. of Psychiatry, UCSF, and was named a Life Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association. He retired from private practice at the age of eighty. He and his wife, Alexandra, continue to make their home in Sausalito, California, where they have lived since 1959. They count two daughters, two sons-in-law, and three grand-daughters among their blessings. He considers himself a very lucky man.

The above written information was provided to me by Dr. Lederer himself. I wish to thank him for his service during WWII and his assistance with this project.