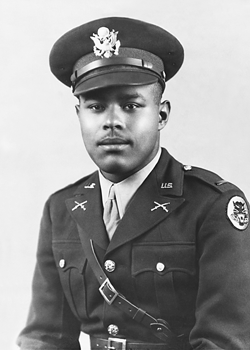

Charles L. Thomas

Charles L. Thomas

The following article was written by Warren Cohen and appeared in the Michigan History Magazine in 1997. We have edited the article to include updated information that has become available since it originally published. Any new information has been identified by underlining. We also deleted a line refering to Sherman tanks used by the unit. The 614th used M5, 3 inch towed anti-tank guns throughout their time overseas.

Recognizing Valor – Profile of Charles Thomas, African-American World War II hero

The black soldier sat uncomfortably stiff, resembling his right arm that was choked tightly in a sting Captain Charles Thomas was at the center of attention, which, with the noticeable exception of the battlefield, was his least favorite spot. A throng of Detroit’s black and white civic leaders stood and thunderously cheered the twenty-four-year-old war hero who had returned home injured from combat at the French-German border at the March 1945 celebration, Thomas became the second black soldier to receive the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second highest honor. In front of his admirers the soft-spoken serviceman played down his heroics. “I was just trying to stay alive out there” he remarked.

His fellow soldiers and officers weren’t as modest. They believed Thomas deserved the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military tribute. The award is rarely given. Of the tens of millions of Americans who have served in the U.S. armed forces since the Civil War (when the medal was introduced), only 3,401 have received the tribute.

But Thomas’ bravery, along with other courageous acts by the 1.2 million African-American soldiers who fought in World War II, was ignored by a military establishment rife with racial prejudice. The armed forces had reluctantly drafted black soldiers after civil rights leaders and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt forced Congress to pass legislation ending discrimination in the military. Despite their eagerness to serve, black soldiers were frustrated by being placed in segregated units that were kept behind the fighting lines to perform medial tasks like cooking or driving. Such policies prevented many blacks from exhibiting heroism in battle. Those that did, like Thomas, were never properly recognized for their valor.

Now, over fifty years later, the military has rectified its long oversight. Early in 1995, following a three-year study by a Pentagon-selected team of historians, seven African American soldiers, including Thomas, were chosen to receive the Medal of Honor President Bill Clinton announced he will bestow the awards on 13 January 1997 during a ceremony at the White House.

Thomas-the fourteenth Michigan veteran of World War II to receive the Medal of Honor-died of cancer in 1980 at the age of fifty-nine. But his heroism was well recognized by Detroit citizens during the war. His deeds were plastered on the front page of the Michigan Chronicle, Detroit’s African American weekly newspaper, and in the city’s other dailies. Yet after the war, Thomas never boasted about his decorations. His military years were rarely discussed, even with friends and family. Thomas’ nephew, Ronald Williams, said, “When I found out he was a hero, I tried to get him to talk about it but he wouldn’t.”

Charles Leroy Thomas was born on 17 April 1920, in Birmingham, Alabama. His family soon moved to Detroit at a time when the city’s black population was rapidly growing. As a child, Thomas showed a bookish interest in planes and electronics. After graduating from Cass Technical High School in 1938, he worked with his father at the Ford River Rouge factory making steel. He also enrolled at Wayne State University to study mechanical engineering but the war interfered. Thomas was drafted and entered the army on 20 January 1942.

He was drafted and entered the service at Fort Custer, Michigan, on January 20, 1942, taking

his basic and advanced infantry training at Camp Wolters in Texas. At some point after his

training at Camp Wolters, Thomas was assigned to the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion, a unit

where the soldiers were black, but most of the officers were white, at Camp Carson,

Colorado. The 614 th arrived at Camp Bowie, TX, on December 18, 1942. Sergeant Thomas was selected for Officer Candidate School (OCS) at Camp Hood, TX, graduating as part of Class #21 on March 11, 1943. He then returned to the 614 th which was soon assigned to Camp Hood on March 23, 1943. Thomas noticed the stark differences between the 614th and white units. Black units were forced to use older, less efficient equipment that frequently needed repairs, and recreational facilities were nonexistent for black soldiers and officers.

Officer Candidate School – Training Documents

After training for two years, Thomas and his troops, weary of endless practice maneuvers, were eager to fight. Finally, in August 1944 the unit was shipped to Metz, France, to join General George Patton’s Third Army. Thomas was pleased when “Old Blood and Guts” declared that he didn’t care if they were black or white, he just wanted fighting men. This task, however, was made difficult by the army’s disbursement of faulty equipment, a fact Thomas attributed to discrimination. (See note at beginning of article)

In December the 614th reached the Alsace-Lorraine region near the German border. Its mission was to capture the German-occupied town of Climbach five miles from the French-German border. The only direct route to Climbach was up a hill along an open road surrounded by woods. An advancing unit would have to distract German guns by traveling up the exposed hill while foot soldiers would sneak through the woods, around the German fire and into the town The approach left the American troops easy targets for German snipers.

Thomas volunteered to lead his company up the hill. “Why did I volunteer?” he recalled in an oral history contained in Mary P. Motley’s The Invisible Soldier: The Experience of the Black Soldier: World War Two. “I can’t honestly answer that…perhaps somewhere in the back of my mind was the fact that we had the only guns that could match the firepower of the Mark VI tanks.”

On the foggy morning of December 14, Thomas led a 250-man company up to the road in an armored scout car. As soon as the unit had advanced, the Germans fired a lethal combination of tank and artillery fire. One blast shattered the scout car’s window, spraying Thomas with glass and metal shears. The next round blew the tires off the car. Although badly injured, Thomas scrambled onto the top of the vehicle, grabbed a .50 caliber machine gun and returned fire.

Suffering wounds in the chest, stomach, arms and legs, Thomas crawled under the overturned car and directed the placement of his men. His men tried to evacuate him but Thomas refused until he was sure that they were well-positioned and returning fire. “This was hardly the place to…I knew what had to be done,” Thomas recalled. “They say men under stress can do unusual…I know I hung onto one thought, deploy the guns and start firing or we’re dead.”

Bogged down for five hours, the Americans ultimately wore the Germans out. Because the Germans were so engaged in fending off Thomas’ men, the Americans crept through the woods and captured Climbach. The stunning victory exacted a heavy toll: more than half of the 614th suffered casualties. Colonel John Blackshear, a white commander, said the actions of the 614th were “the most magnificent display of mass heroism I have ever witnessed.”

Thomas refused to take credit for his heroics, believing his soldiers deserved the accolades. Nevertheless, one week after the battle, Colonel Blackshear recommended Thomas for the Distinguished Service Cross. The award was announced in January 1945 and Thomas was promoted to captain. His unit was commemorated as well, becoming the first black battalion to win a distinguished unit citation. The men of the 614th also received eight silver stars, twenty-eight bronze stars and seventy-nine purple hearts.

(The photo below shows Thomas receiving his Distinguished Service Cross from

Brigadier General Joseph E. Bastion in 1945.)

The 614th continued across Germany and Austriabut Thomas’ injuries permanently ended his combat duties. After he was sent to a hospital in England, Thomas went to Percy Jones Hospital in Battle Creek for further rehabilitation. Discharged from the army in 1947 with the rank of major, Thomas received disability payments for the rest of his life. He lost parts of his right arm and three fingers on his right hand, unable to bend, were forever set at an angle. Friends say that his stomach resembled a road map with all of his stitches.

The 614th continued across Germany and Austriabut Thomas’ injuries permanently ended his combat duties. After he was sent to a hospital in England, Thomas went to Percy Jones Hospital in Battle Creek for further rehabilitation. Discharged from the army in 1947 with the rank of major, Thomas received disability payments for the rest of his life. He lost parts of his right arm and three fingers on his right hand, unable to bend, were forever set at an angle. Friends say that his stomach resembled a road map with all of his stitches.

In July 1949 Thomas married Bertha Thompson, a waitress at a local restaurant. -They had two children, Linda and Michael (Linda died young of cancer in 1962). Michael recalled that as a boy, when he and his father ran into old soldiers in Detroit, some of them were convinced Thomas had died at Climbach. “People who saw him thought they saw a ghost,” he said.

Thomas worked at Selfridge Field in Mount Clemens as a missile technician. He later became interested in computers and his last job was as a programmer for the Internal Revenue Service. He also took classes at Wayne State University, falling just short of a degree in mechanical engineering. In his spare time Thomas tinkered under the hood of a car or worked in the family’s basement building televisions from spare parts.

While Thomas remained silent about his war exploits, his right arm had withered noticeably. He usually kept it close to his side and never admitted to any pain. That disability was the sole mark of his years in the military. Thomas eschewed veterans groups and that, along with his modesty, caused people to slowly forget his accomplishments. When he died, the newspapers whose headlines once trumpeted his heroism neglected to run an obituary. Thomas’s posthumous Medal of Honor will give this courageous soldier the recognition he shunned but deserved.

The following is the Thomas’ citation for the Medal of Honor:

For extraordinary heroism in action on 14 December 1944, near Climbach, France. While riding in the lead vehicle of a task force organized to storm and capture the village of Climbach, France, then First Lieutenant Thomas’ armored scout car was subjected to intense enemy artillery, self-propelled gun, and small arms fire. Although wounded by the initial burst of hostile fire, Lieutenant Thomas signaled the remainder of the column to halt and, despite the severity of his wounds, assisted the crew of the wrecked car in dismounting. Upon leaving the scant protection which the vehicle afforded, Lieutenant Thomas was again subjected to a hail of enemy fire which inflicted multiple gunshot wounds in his chest, legs, and left arm. Despite the intense pain caused by these wounds, Lieutenant Thomas ordered and directed the dispersion and emplacement of two antitank guns which in a few moments were promptly and effectively returning the enemy fire. Realizing that he could no longer remain in command of the platoon, he signaled to the platoon commander to join him. Lieutenant Thomas then thoroughly oriented him on enemy gun dispositions and the general situation. Only after he was certain that his junior officer was in full control of the situation did he permit himself to be evacuated. First Lieutenant Thomas’ outstanding heroism were an inspiration to his men and exemplify the highest traditions of the Armed Forces.

Charles Thomas died on February 15, 1980, and was buried in the Westlawn Cemetery in Wayne County Michigan. On January 19, 1997, Thomas’ Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal of Honor and was presented to his family by President Bill Clinton.

Charles Thomas died on February 15, 1980, and was buried in the Westlawn Cemetery in Wayne County Michigan. On January 19, 1997, Thomas’ Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal of Honor and was presented to his family by President Bill Clinton.

Thank you to Randy Dunham for the additional documents regarding Thomas’ OCS Training and service time.